EAGER fish conservationists found out Hungry Birds is more than just a computer game after fish-stocking efforts were thwarted recently.

The plan had been to release 10,000 endangered Mary River Cod fingerlings into the Bremer River at Rosewood’s Armstrong Park.

But peckish cormorants keen on a feed put a dent in the conservation bid when they chomped their way through 7,500 fingerlings at stocking ponds the previous evening.

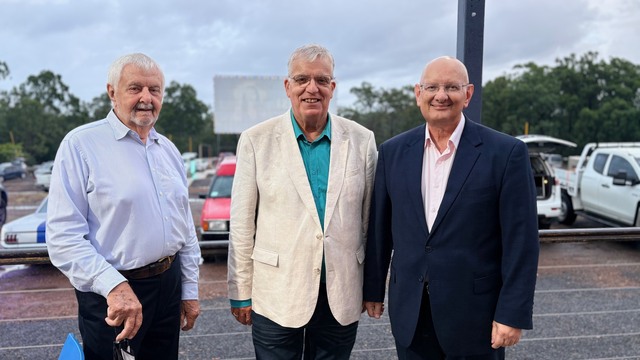

Somerset and Wivenhoe Fish Stocking Association (SWFSA) president Garry Fitzgerald was leading the mission.

“It wasn’t the best news to wake up to, but any release of Mary River Cod is incredibly worthwhile,” Mr Fitzgerald said.

“There will be more releases to come over coming months.”

The fingerlings will now work their way through local waterways.

He said the recent rainfall had provided perfect conditions.

“We were lucky to have had good rain because the rivers flowed again, whereas a couple of weeks ago they were dry – it was perfect timing.

“The extra river flow stirred up the water nicely and triggered blooms of zooplankton which the fish eat.”

He said fish restocking must continue into the 2030s to lift numbers.

“If females don’t have enough choice in breeding partners, they tend to not mate.”

About 18,000 Mary River Cod were last year released into the Bremer River catchment.

“Our hope in the years ahead is to have an established, self-sufficient population of cod in the Bremer catchment with annual stockings to continue,” Division 4 Councillor Russell Milligan said.

“Being such a large-bodied fish, these adult cod will contribute to the management of pest fish in the system such as tilapia and carp.”

The Endangered Fish Stocking Program will next centre its efforts on the Brisbane River.

The Mary River Cod is particularly territorial, staying within its defined territory 98 percent of its life and leaving only to feed and breed.

Incredibly abundant before European settlement, Mary River Cod were then overfished – sometimes even with explosives – with the fish often used as pig feed.

Overfishing, huge silt deposits caused by land clearing, and dams and weirs blocking migration decimated numbers of the large, slow-growing, long-lived species which can reach more than 100 years old.

The species now occurs in less than 30 percent of its historic range.

In the 1980s, just 600 individuals survived in the wild.